Silhouettes: Outlining history

Silhouettes are usually made of cut paper on a contrasting background and then framed, although one can also see silhouettes in photography as well as other media.

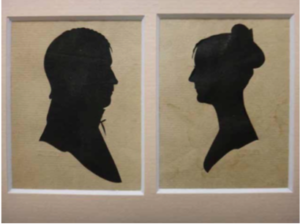

(Photo courtesy DeeDee Wood)

Silhouettes are thought of as a featureless side view of a person, with a backdrop of white or cream, usually in an old antique frame with some sort of historical value.

Really, a silhouette is simply a person, animal, object or scene that is a solid black shape with the edges representing the outline of the thing that it is depicting.

The inside, or interior of the silhouette is without feature, and is usually presented on a light-colored background.

The silhouette appears as a solid shape, giving the idea of the features that you will never see.

Silhouettes are usually made of cut paper on a contrasting back- ground and then framed, although one can also see silhouettes in photography as well as other media.

The term “silhouette” comes from the name Etienne de Silhouette, a French nance minister from 1759 who imposed severe economic demands upon the French people during the Seven Years’ War credit crisis.

His name became associated with anything done cheaply, and thus, the paper cutouts of a person’s face were considered a very cheap way to record appearance.

Since photography had not been invented, this was certainly the most cost-effective way to record the history of what someone appeared to be in the real world.

Although the term “silhouette” existed in the 18th century, it wasn’t really applied to the art of portrait- making until later in the 19th century.

Silhouettes were also referred to as profiles or shades and were made in various ways.

The most popular way to make one was to cut it out of black paper free-hand style with scissors and paste it onto a light background.

They were also painted on cards, plaster and glass.

There was also a technique called hollow cut, where a negative image was traced and then cut away from a lighter color of paper, thus creating a negative image.

A silhouette can be painted or drawn, but the tradition is to cut them from lightweight black cardboard and mount them on a white background.

Specialty artists often worked at markets and places people gathered to sell their art and talents to people who wanted to capture their likeness.

A silhouette artist usually worked freehand, using only their eyes to see the outline, and could complete one in a few minutes.

The silhouette was an alternative to expensive miniature portraits that were painted, offering a far cheaper way to preserve history.

There have been silhouette artists all over the world who were noted for their work.

The 18th century silhouette artist August Edouart cut thousands of portraits in his time.

His subjects were nobility of Europe and U.S. presidents.

In England, a silhouette painter named John Miers worked in many cities capturing the likenesses of people. He advertised “three minute sittings.”

Frenchman Gilles-Louis Chretien invented a machine that could produce many silhouettes called a physionotrace. It was created by using a tracer, engraving and copying.

Many of these artists made portraits so small they could t into a locket. The invention of photography was the end of widespread silhouette making for artists.

There is also a type of silhouette that depicts scenes that are called “paper cuts.”

An entire scene of some activity was depicted, such as a child taking out a pale to feed the geese on a windswept farm hill.

Among the 19th century artists who worked paper cuts was the famous author Hans Christian Andersen.

Many paper cut silhouettes depicted scenes much cheaper this way, and one could find them popping up in 19th century popular children and adult literature of the time.

An artist only had to use one color of ink and print an entire scene for cheaper than a full color painting or print.

A block was used that could be printed over and over.

They were cheaper and much easier to use than the more expensive black and white illustrations.

The skill and art of silhouette lives on today.

Artists can still be seen at state fairs drawing and cutting silhouettes of customers.

Antique collections go for big money as well on online auction sites, showing the popularity of the paper cuts has not been lost to time.

Many silhouette businesses service the wedding industry and other family-specialty functions where memories should be unique.

Shades had their heyday in a world that had no photography.

Hand-cut paper, a subject, and a little talent created a lasting record of what people, animals and places looked like, if only a glimpse of shadow, only an outline of what once was.

Necessity is the mother of invention, they say, and silhouettes certainly were popular as an alternative, cheaper way to preserve history in paper.

(Editor’s note: DeeDee Wood is the store manager at arpe Antiques, in Easton, part of the Talbot Historical Society.)