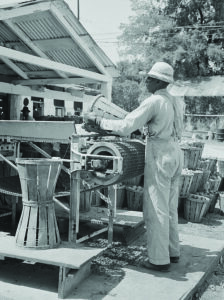

At its peak, the Delmarva canning industry provided up to 15,000 jobs, paying workers as much as $5 per day, which for the time, was a decent wage. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress)

Whether picked from your garden or purchased from local produce stands, fresh tomatoes are hot off the vines this time of year across Maryland.

At their peak, fresh tomatoes are prepared in a number of ways such as in gazpacho, salsas, sauces and salads, while many are canned to preserve for future use.

Although canning has been done in many households over the years, canneries represented the principal manufacturing industry on the Delmarva Peninsula from 1880 into the 1950s.

Originally started as a means to extend the selling life of oysters and fruits, canning was adapted to tomatoes soon after, when inexpensive tin cans became widely available from Baltimore’s manufacturing plants.

Canneries could be found in Maryland towns such as Hurlock, Preston, Princess Anne, Pocomoke, Ridgely, Trappe, and Cambridge.

During the early 1900s, Dorchester County claimed itself the leader in terms of productivity, packing almost 1.1 million cases of tomatoes versus Caroline County — runner up with almost 750,000 cases.

Tomatoes were harvested from nearby farms, and many of the facilities were located close to railroads and rivers for shipping.

Canneries were serviced by local farmers who transported their lot of ripe tomatoes in skipjacks, buyboats, and farm carts.

At one time, during the 1920s, a Delaware cannery, Greenabaum, claimed to be the largest in the world, touting a capacity of 10,000 baskets of tomatoes a day.

Barges brought tomatoes to Seaford via the Nanticoke River that had been collected from farms up and down the Chesapeake Bay side of the peninsula.

One of the area’s existing stand-out companies, Phillips Seafood, in Cambridge, Md., was actually created from the tomato packing industry.

Established in 1902, Phillips Packing and Seafood Company was one of the largest food processors in the nation.

Phillips was primarily known for tomato canning and ketchup, but also packed fruit, vegetables, oysters and crabs.

During World War II, the company was responsible for supplying K and C rations to U.S. troops, hiring women, and non-U.S. immigrant labor to meet production demands.

As their canning business waned, the family expanded into the seafood side of the business.

The packing plant was ultimately sold to Consolidated Foods in 1956.

At its peak, the Delmarva canning industry provided up to 15,000 jobs, paying workers as much as $5 per day, which for the time, was a decent wage.

Tokens of pay, called merchant tokens, were widely used on the Eastern Shore after the Civil War to pay laborers that picked or packed vegetables, fruit, oysters, crab, and the like.

The tokens were made of copper, brass, fiber, or aluminum planchet (round metal disc), simply stamped with the canner’s initials and a denomination such as 1 Bkt (bucket) or 1 Bas (basket).

Redeemable on payday, the tokens were distributed as a “unit of work”, some having holes punched in them for easy keeping.

Merchant tokens, along with colorful old cannery labels, are now popular as collection items.

During the late 19th to early-20th-centuries, skilled lithographers created labels for packing companies to attract customers’ attention and to ultimately, purchase their product.

The can label for Defender Brand Tomatoes of Trappe, Md., was designed by Simpson and Doeller, a prominent lithograph company out of Baltimore. The client’s eye-catching label features a vibrant tomato on the front side, and what appears to be a skipjack at sea on the back.

Akin to its label, today’s variety of the tasty Defender tomato yields a beautiful, smooth fruit with excellent taste and uniformity.

Defender Packing Company was established by brothers Anthony Bennett Adams, Sr. and George Francis Adams just north of the town of Trappe around 1910.

The company prospered, packing peeled tomatoes in three different size cans, later adding packed cream style corn to the mix.

The late 1920s and ’30s would bring hard times to the canning industry, but Defender Packing Company managed to hang on until about 1950 with the canning of both tomatoes and sweet corn grown by local farmers and a labor force derived from area residents and migrant workers.

The cannery once operated next door to what was appropriately named Defender House — Trappe’s Rural Life Museum’s headquarters and anchor building.

Unfortunately, canneries across the region began to decline in the 1950s due to competition from other warm weather states with longer growing seasons.

Adding to their demise was the consolidation of canning brought about by labor conflicts and advances in refrigerated shipping, squeezing Delmarva’s smaller operations out of business.

But the mighty tomato, canned or not canned, lives on!